Recovery, rehabilitation, and Berlin Heart Excor decannulation in tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy presenting with cardiogenic shock

Lauren Glass1, Jeremy Affolter2, Daniel Stromberg2, Ken Schaffer1, Chesney Castleberry1, Richard Owens4, Amanda Thompson4, Sujata Subramanian4, Erin Gottlieb3, Charles Frasier4.

1Cardiology, Dell Children's Hospital, Austin, TX, United States; 2Critical Care, Dell Children's Hospital, Austin, TX, United States; 3Anesthesiology, Dell Children's Hospital, Austin, TX, United States; 4Cardiothoracic Surgery, Dell Children's Hospital, Austin, TX, United States

Introduction: Permanent junctional reciprocating tachycardia (PJRT) is a rare, incessant form of pediatric tachyarrhythmia, associated with cardiomyopathy in up to 20% of patients. Many patients require electrophysiologic catheter ablation due to pharmacologic treatment failure. Patients with PJRT may require mechanical circulatory support due to tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy. We present a 4-year-old female patient presenting in cardiogenic shock due to newly diagnosed PJRT, requiring cannulation for mechanical circulatory support and later decannulated after recovery.

Case Report: A 4-year-old female with mild asthma presented to the emergency department with dyspnea. She had severe cardiomegaly on chest radiograph and an electrocardiogram demonstrating PJRT (HR 195 bpm). Echocardiogram revealed severe left ventricular dysfunction (ejection fraction < 10%). The patient was electively intubated in the operating room, with cardiothoracic surgery and mechanical support teams on standby. She underwent successful emergent catheter ablation of the PJRT pathway. However, residual poor ventricular function, inotropic dependence, and ventricular ectopy led to placement of a temporary left ventricular assist device. Due to lack of recovery, she was transitioned to a Berlin Heart Excor left ventricular assist device (VAD) and listed for cardiac transplantation.

She underwent extensive cardiac rehabilitation over the next months, and organ dysfunction resolved. She did not have PJRT recurrence, and ventricular ectopy significantly decreased. She experienced a self-resolved transient ischemic attack requiring pump exchange.

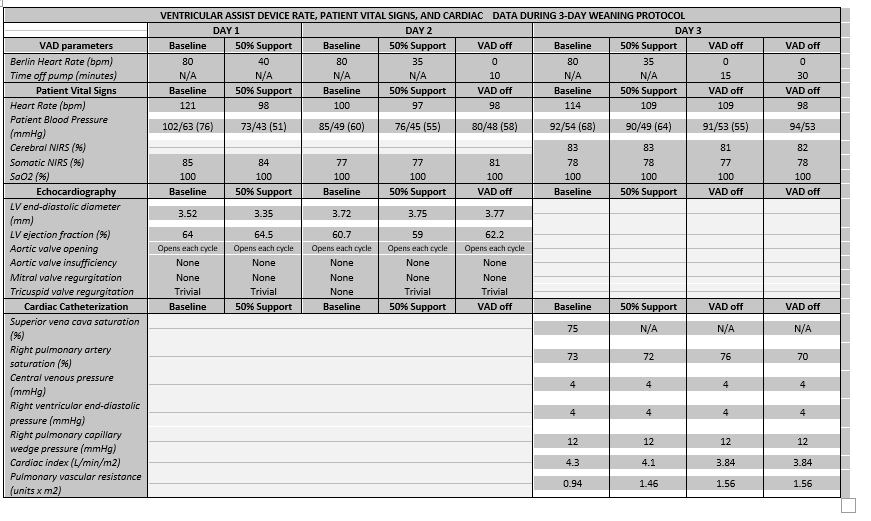

With sustained clinical improvement and left ventricular recovery, VAD decannulation was considered. Criteria included normalized left ventricular end-diastolic diameter and left ventricular ejection fraction (60%), aortic valve opening with every beat, trivial atrioventricular valve regurgitation, and sinus rhythm. She underwent weaning studies, modified from Berlin Heart and ACTION resources, over 3 days (Table 1). The patient was transitioned from bivalirudin to heparin while weaning.

Upon obtaining favorable data, the patient was successfully decannulated 147 days after VAD placement. She was discharged one week later, with discharge echocardiogram demonstrating normal left ventricular size and function, on carvedilol, lisinopril, spironolactone, and aspirin.

Discussion: Berlin heart decannulation in the pediatric population remains a scarce occurrence. Optimal mechanical support offered cardiac and systemic recovery in this patient, with successful transition to an outpatient enteral therapy regimen. Modified wean trial performed was useful in anticipating successful decannulation in this patient.

Conclusion: Continued accumulation of experiences is necessary to determine candidacy for Berlin Heart decannulation, relating to patient criteria and timing, weaning protocols, and therapy after decannulation.