Reduction of waiting time and waiting list mortality for paediatric liver transplantation following introduction of an intention-to-split allocation policy

Helen Evans1,3, Stephen Mouat1, John McCall2,4.

1Department of Paediatric Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Starship Child Health, Te Toka Tumai, Te Whatu Ora, Auckland, New Zealand; 2New Zealand Liver Transplant Unit, Te Toka Tumai, Te Whatu Ora, Auckland, New Zealand; 3Department of Paediatrics: Child and Youth Health, School of Medicine, The University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand; 4Department of Surgery, School of Medicine, The University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand

Introduction: New Zealand (NZ) commenced a national paediatric liver transplant (LT) programme in 2002. While patient and graft survival is comparable to similar countries, early experience showed that waiting list (WL) time and WL mortality were higher than expected. A formally agreed intention-to-split deceased donor organ allocation policy was introduced in 2016 whereby all suitable organs from donors of 40 years and below are split between a paediatric and adult recipient. When splitting is not technically possible, the organ is directed towards the paediatric recipient. The aim of this study was to analyse the response in WL time and WL mortality following introduction of the policy.

Methods: All paediatric patients listed for LT during eras 2002-2015 (before the intention-to-split policy) and 2016-2022 (after policy introduction) were identified using the national LT database. WL times and mortality were compared between eras as were rates of live donor LT (LDLT) and deceased donor LT (DDLT). Descriptive statistics were used to compare results.

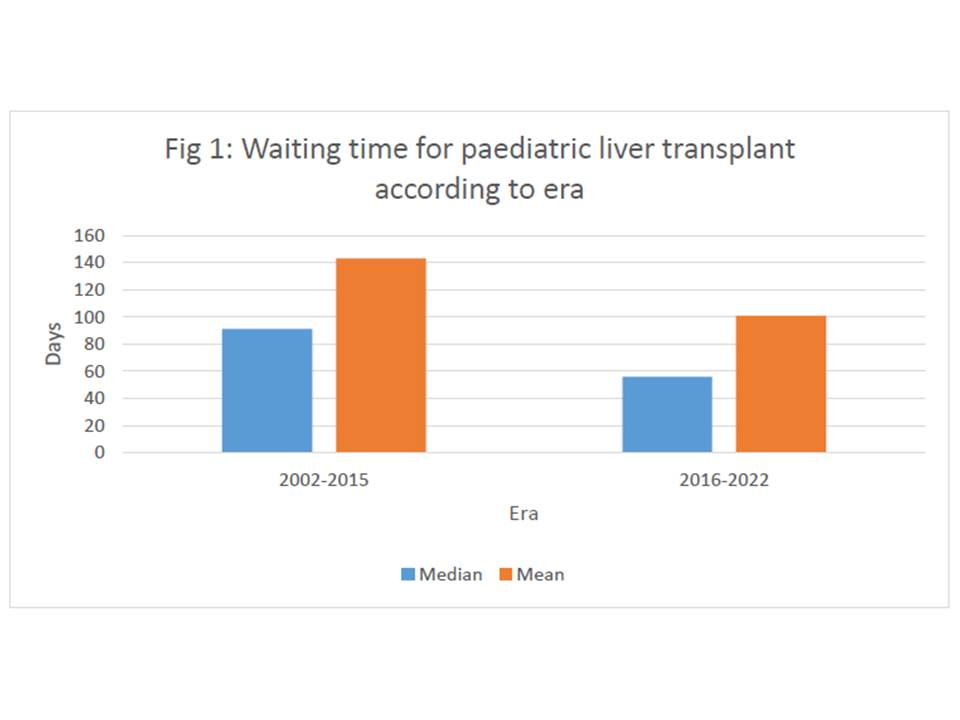

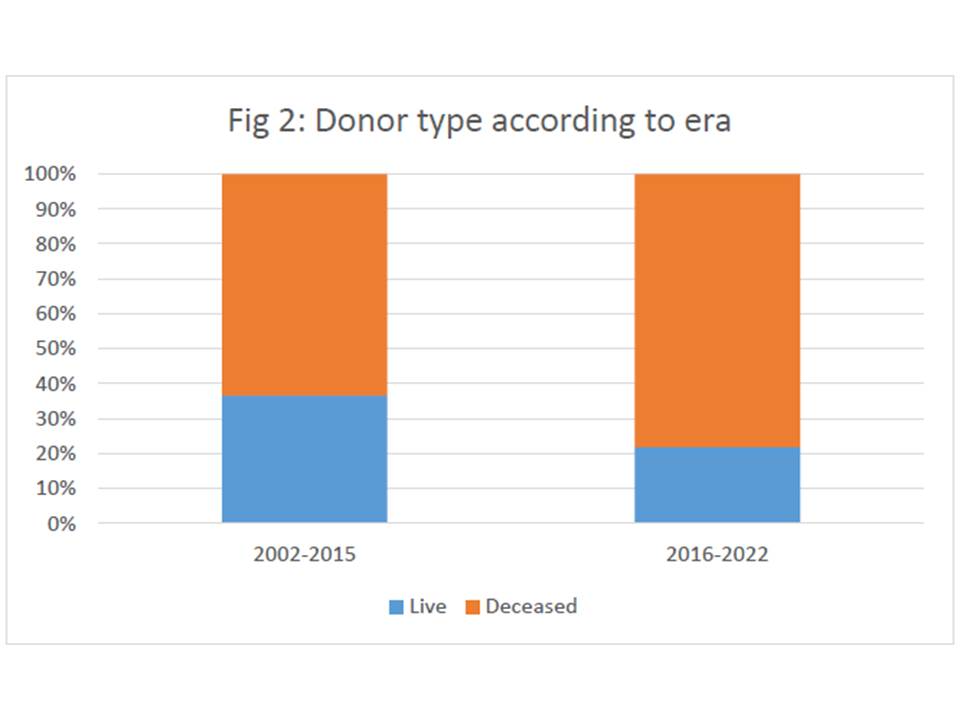

Results: Between 2002-2015, 132 children (66F;66M; median age 1.2 years (0-16.5)) were listed for LT, of whom 120 were transplanted at a median WL time of 91 days (mean 143 days). 44 (36.7%) children underwent LDLT. 12 children (9.1%) died on the WL. Indigenous Māori (5) and Pacific (2) children (representing 17% and 9% of the general NZ population) were over-represented in the WL deaths. Four of the children died awaiting LT for acute liver failure (ALF).

From 2015-2022, 67 children (40F; 27M; median age 2.1 years (0-17.4)) were listed for LT, of whom 64 were transplanted at a median WL time of 56 days (mean 101 days). 14 (21.9%) children underwent LDLT. 3 children (4.4%, 1 Māori, 1 Pacific and 1 European)) died on the WL, none of whom had ALF.

There were statistically significant reductions in median and mean WL times (p<0.05; Fig 1)) and use of LDLT (p<0.05; Fig 2)). WL mortality failed to reach statistical significance due to small numbers. There was no adverse effect on WL times or mortality for adults undergoing LT.

Conclusions: The introduction of a formal intention-to-split deceased donor allocation policy to prioritise children awaiting LT in NZ has resulted in an early and significant reduction in WL times and mortality as well as reliance on live donor LT. The policy may have also benefitted children with ALF and Māori and Pacific children. Longer-term evaluation will be necessary to ensure these early reductions are maintained.

Organ Donation New Zealand.