Caroline P. Lemoine, United States

Pediatric transplant and hepatobiliary surgeon

Division of Transplant and Advanced Hepatobiliary Surgery

Ann & Robert H Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago

What is the impact of donor quality on outcomes after pediatric split liver transplant?

Caroline Lemoine1, Katherine Brandt1, Juan Carlos Caicedo1, Riccardo Superina1.

1Division of Transplant and Advanced Hepatobiliary Surgery, Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago, Chicago, IL, United States

Introduction: In order to minimize possible adverse consequences of splitting a liver for transplantation into two recipients, criteria have been established to select the best possible organs for split liver transplants (SLT). Decisions at our center about the suitability of a donor liver for splitting are made using both UNOS criteria and modified local criteria. We hypothesized that outcomes after pediatric SLT are not different when using ideal (ID) vs. non-ideal (nID) donor criteria.

Methods: We reviewed 96 SLT performed at our institution between 02/2004 and 02/2022. Thirty-seven split transplants were excluded due to incomplete donor information. ID were defined according to UNOS criteria: age <40 years, body mass index (BMI) <28, AST/ALT <3 times normal, 0-1 vasopressor. Our institutional criteria were similar except for: age <45 years, <5 days in the ICU. Results in ID and nID were compared according to complication rates, and patient (PS) and graft survival (GS). Lastly, comparisons between the early (2004-2014, n=49) and modern (2014-2022, n=47) eras of our program were performed. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

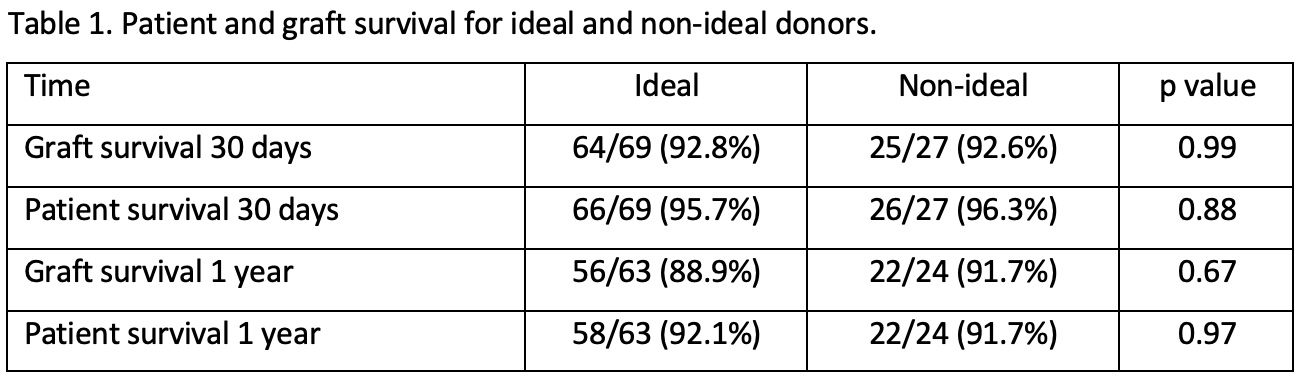

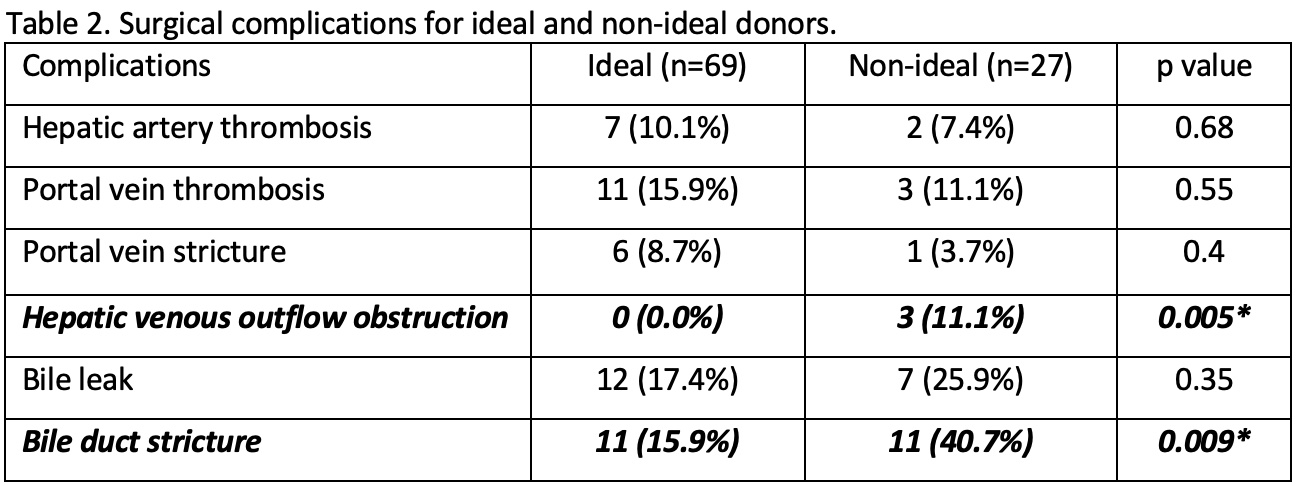

Results: Ninety-six SLT were performed in 94 children, of which 93 were first transplants and 3 were re-transplants. Sixty-two of 96 (64.6%) were segment 2-3 grafts. Using UNOS SLT criteria, 70/96 donors were considered ID (72.9%). Twenty-one of 26 nID (80.8%) had only one discordant criteria from the 4 UNOS criteria. The most frequent non-adhered to criteria was vasopressor support (2 vasopressors in 13 cases) and BMI >28 in 11 cases (ranging from 28.1 to 38.9). Transaminases <3 times normal was the criteria most adhered to, exceeded in only 2 occasions. There was no difference between ID and nID groups in GS and PS at 30-day, 90-day, 1-year, 3-year, 5-year (Figure 1). The overall GS (ID 84.1% vs. nID 81.5%, p=0.92) and PS (ID 91.3% vs. nID 81.5%, p=0.4) were also not-statistically different. When comparing postoperative vascular and biliary complications, hepatic venous obstruction (ID 0/69, 0% vs. nID 3/27, 11.1%, p=0.005%) and bile duct stricture (ID 11/69, 15.9% vs. nID 11/27, 40.7%, p=0.009) were statistically different (Figure 2). Similar results were obtained when using our own institutional criteria. The proportion of ID increased in the modern era of our program, although non significantly (early: 32/49, 65.3% vs. modern: 37/46, 78.7%, p=0.14).

Conclusions: Outcomes after split liver transplantation are similar when using ideal versus non-ideal split liver donors. We propose that vasopressor and BMI requirements can be excluded from UNOS donor selection guidelines for SLT. Non-ideal donors can safely be used for split liver transplantation to help increase the donor pool and the rate of both pediatric and adult liver transplantation and decrease the waitlist mortality.

Robert E Schneider Foundation .

Lectures by Caroline P. Lemoine

| When | Session | Talk Title | Room |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Tue-28 09:10 - 10:10 |

Liver | What is the impact of donor quality on outcomes after pediatric split liver transplant? | Hill Country AB |